Maritime Transport of Oil and Gas: Routes, Ships, and Climate Issues

10 min read

Oil and gas freight accounts for nearly one-third of global maritime trade. Ships that transport and refined products are called oil tankers, while those that transport and are called gas tankers. They travel the world's major shipping routes, passing through strategic locations such as the Straits of Hormuz and the Straits of Malacca, and the Suez and Panama Canals.

© Gonzalez Thierry - TotalEnergies - Oil tanker loading operation near a giant offshore barge

Maritime Freight: a Pillar of Global Oil and Gas Trade

Huge quantities of , refined products, and gas are transported by ship between production sites, refineries, and consumption centers. Oil freight accounts for around 30% of global maritime trade volume.

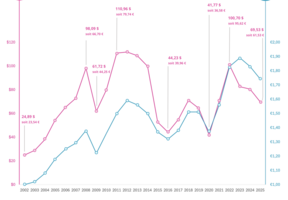

In 2023, crude oil transported by sea amounted to 2.1 billion tons.

The figure for refined products and liquefied gas reached 2.3 billion tons. For several decades, the transport of refined products has been growing faster than that of crude oil, becoming dominant in 2019.

This change is linked to upheavals in the refining industry: the construction of giant refineries in producing countries (particularly in the Gulf), new export capacity in the United States, and growing demand from emerging countries. continued to grow at the same time.

In 2025, the total capacity of the global oil fleet was 670 million tons for more than 12,000 tankers. This capacity more than doubled between 2000 and 2025 to meet growing global demand.

Oil tankers are classified according to their capacity, expressed in “deadweight tons” (maximum cargo capacity of a ship). Crude oil transport fleets consist of VLCCs (Very Large Crude Carriers), with a capacity of around 300,000 tons (equivalent to 2 million barrels), Suezmax (around 150,000 tons and 1 million barrels) and Aframax (from 80,000 to 120,000 tons, approximately 700,000 barrels).

Refined products (gasoline, , kerosene, chemicals, ) are transported in smaller vessels, adapted to the size of the cargo and capable of unloading in numerous ports close to consumers. The largest are called Long Range 2 (LR2) and are approximately 250 meters long.

Gas is transported in liquid form: this reduces its volume by several hundred times and increases the quantities that can be transported. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is transported on board LNG carriers at a temperature of -162°C. The capacity of oil tankers is limited by straits, ports, and canals, which impose maximum widths and drafts. For example, Suezmax tankers must have a draft of no more than 20 meters to be able to use the Suez Canal.

The costs of transporting oil and gas are known as freight costs. They fluctuate according to supply and demand: for the same route and the same ship, they can vary significantly depending on the time of year. These transport costs represent a few percent of the value of oil and gas.

Maritime Routes for Oil and Gas: Strategic Straits and Canals

For crude oil, the busiest routes depart from the Middle East, West Africa, and Latin America. They cross the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, separating Djibouti (Africa) from Yemen (Arabian Peninsula), or the Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf (separating the United Arab Emirates and Oman from Iran), the world's main oil transit point. They then travel for 15 days to a month to reach:

- Asia via the Strait of Malacca, between Sumatra and Malaysia,

- Europe via the Suez Canal or, if they are too wide, via the Cape of Good Hope, then Northern Europe via the English Channel.

LNG carriers follow different routes: they mainly depart from the United States, Qatar, Russia, Australia, and Nigeria and travel to Asia or Europe.

With the increase in Asian demand, the Panama Canal is seeing an ever-increasing volume of oil freight passing through: it was widened in 2016 so that larger ships could use it. Its width increased from 32 meters to 51 meters.

However, these routes are highly sensitive to climatic and geopolitical upheavals. For example, the use of the Suez Canal is largely dependent on the situation in the Middle East, and the Panama Canal has recently experienced periods of closure due to severe drought that caused water levels to fall too low. Sometimes, simple accidents are enough to disrupt maritime routes: in 2021, a container ship ran aground in the Suez Canal and blocked it for six days!

Energy Transition and Regulation: What Does the Future Hold for the Global Fleet?

The global fleet of oil and gas tankers emitted more than 320 million tons of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in 2023 (approximately 1% of annual global emissions).3

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has adopted several environmental regulations since 2010 that have had a tangible impact on ships. For example, regulations (EEDI and EEXI) have contributed to a slowdown in ship speeds. At the same time, the European carbon tax (ETS) and FuelEU Maritime regulations aim to encourage the use of lower-carbon fuels.

New fuels (liquefied natural gas, liquefied petroleum gas, , ammonia, , etc.) have emerged in recent years to meet these new regulations. Energy-efficient equipment that reduces pollution and operating costs is constantly improving. All these new technologies are particularly well suited to oil tankers, which have space available on their decks.

Sources :