Clichy-Batignolles : Eco-District Energy Solutions

5 min read

Imagine a neighborhood with low-energy buildings, where is solar-generated, the heating system is collective, where plants and vegetables are grown, where getting from A to B is simple, and where you can chat away to your neighbors. That’s the purpose of the Clichy-Batignolles eco-district in Paris. Building began in 2010 and will be finished in 2024. It is intended to be a trial neighborhood for the future urban districts of Greater Paris, with its 131 cities and population of 7.2 million.

© HANS LUCAS VIA AFP - View of the Clichy-Batignolles district from the solar-panel-covered roof of one of the new buildings

Located between the Paris ring road”, "Porte de Clichy” and the Batignolles Quarter, the eco-district integrates several new apartment blocks built to the most stringent environmental standards, boasts a heating system, photovoltaic units and wide expanses of green spaces.

Construction of the district culminated in 2020 with the development of the "Porte de Clichy”1 around the imposing buildings of the new Law Courts and the French Criminal Investigation Department (Direction générale de la Police judiciaire) in Paris. Both buildings moved to Clichy from their original location in the “île de la Cité”, and the renowned “Quai des Orfèvres”. The “Stream building” apartment block was inaugurated in 2023, and is intended to be a symbol of sustainable architecture, with its wooden structure, green walls, urban rooftop farms and production of hops for a local beer. The 20,000 liters produced every year are to be drunk only on site!

Economy of Resources, the No.1 Priority

The eco-district’s goal is to ensure that 85% of its heating and domestic hot water is supplied by sources, primarily geothermal. To achieve this, it is necessary for the buildings to be properly insulated. Paris City Hall has established a 15 kWh/sq.m/year heating limit for Clichy-Batignolles based on an indoor temperature of 18°C. It’s a very strict standard, considering that a Parisian building with poor insulation, like many red brick structures on the outskirts of the city built during the two world wars, can consume up to 10 times more energy. Moreover, many people are accustomed to setting the thermostats of their homes and offices above 18°C.

Geothermal Heat

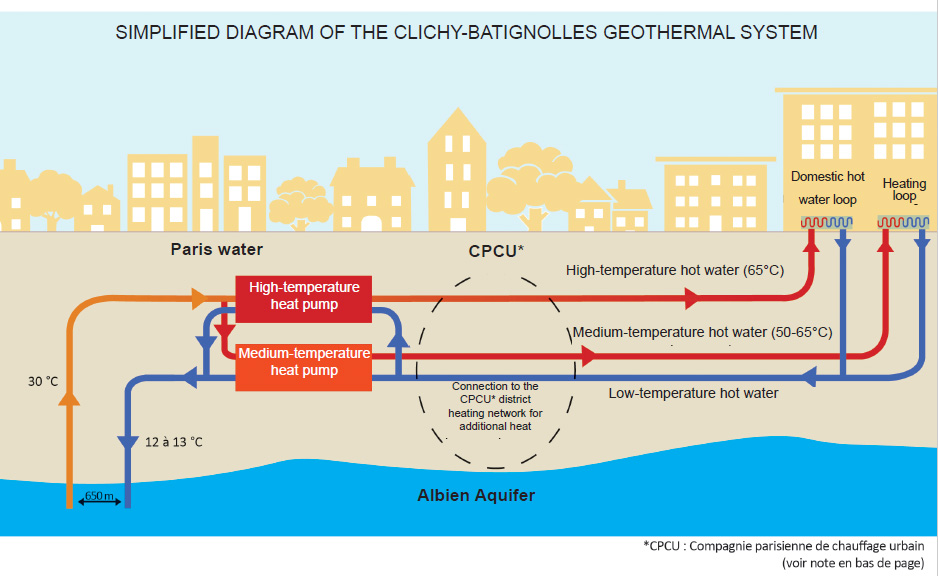

The eco-district will be supplied by geothermal heat drawn from the 600-meter-deep Albien , which flows for about 80,000 square kilometers beneath the Paris Basin. Once used intensively for various industrial and artisanal applications, the aquifer is now carefully controlled since it’s the city’s emergency drinking water reserve. There are five wells within Paris proper. When municipal water service operator Eau de Paris drilled a sixth well, it was decided to use it to create an open-to-recycle system, also known as a doublet earth coupling. A second well was therefore drilled roughly 600 meters from the Eau de Paris extraction well so the used water could be injected back into the ground.

In an open-to-recycle system, heat from hot water pumped from the ground is extracted and used to heat buildings. The used water is then returned to the aquifer. In the case of Clichy-Batignolles (see diagram below), the water collected from the Albien aquifer has a temperature of about 30°C. Heat pumps are used to raise the water temperature to 65°C for the production of domestic hot water or to a slightly lower 50-65°C for district heating purposes.

A series of heat exchangers connected to the district heating network, which is run by (CPCU)2, provide additional heat if necessary. One of the difficulties associated with a geothermal system is that it provides a steady supply of heat, whereas demand varies greatly depending on fluctuations in outside temperature.

The water is pumped through small heat exchangers and the extracted heat is transferred to the building’s heating system. The used water is then pumped back to the geothermal reservoir at a temperature of 12-13°C. All of the water is thus returned to the aquifer without any change in quality.

The heat exchange station was built 10 meters below the Earth’s surface in order to protect the environment and save space, since the price per square meter in the French capital is very high.

Solar Photovoltaic Electricity

Clichy-Batignolles is also committed to producing energy from 35,000 sq.m of solar panels installed on building rooftops and facades. The goal is to generate 4,500 MWh per year, or 1,000 times the average electricity consumption of a French household.

Rounding out its green credentials, the new urban area has developed many leafy areas (the centrally located Martin Luther King Park has 14 access points) and a road network adapted to eco-friendly mobility solutions (bicycles, scooters) and public modes of transportation. Thanks to an innovative trash disposal system, there are no longer any garbage trucks maneuvering the streets. Rubbish placed in containers at the foot of the buildings is automatically removed by an underground pneumatic system.

Digital Monitoring

Digital analyses are used to manage energy in the new district. Smart-E is a platform that records the energy consumption of each building on an hour-by-hour basis, for each type of equipment: heating, lighting, kitchen appliances, laundry, use of consoles and computers, television, etc. and everything is modeled at district scale. Based on this model, the district population will be informed about the ecological actions they can take and, in parallel, studies will be conducted to balance heat and electricity supply and demand as effectively as possible.

- Clichy-Batignolles (Paris 17th) | Paris & Métropole Aménagement (parisetmetropole-amenagement.fr)

Compagnie Parisienne de Chauffage Urbain. CPCU manages the heating network of the greater Paris area and is Europe’s seventh largest operator. It supplies heat to one and a half million Parisians via a 510-kilometer network. In 2017, CPCU’s was more than 50% renewable and recovered energy (mainly household waste together with wood), 30% natural gas and 16% . Geothermal energy still accounts for less than 1% of the total.